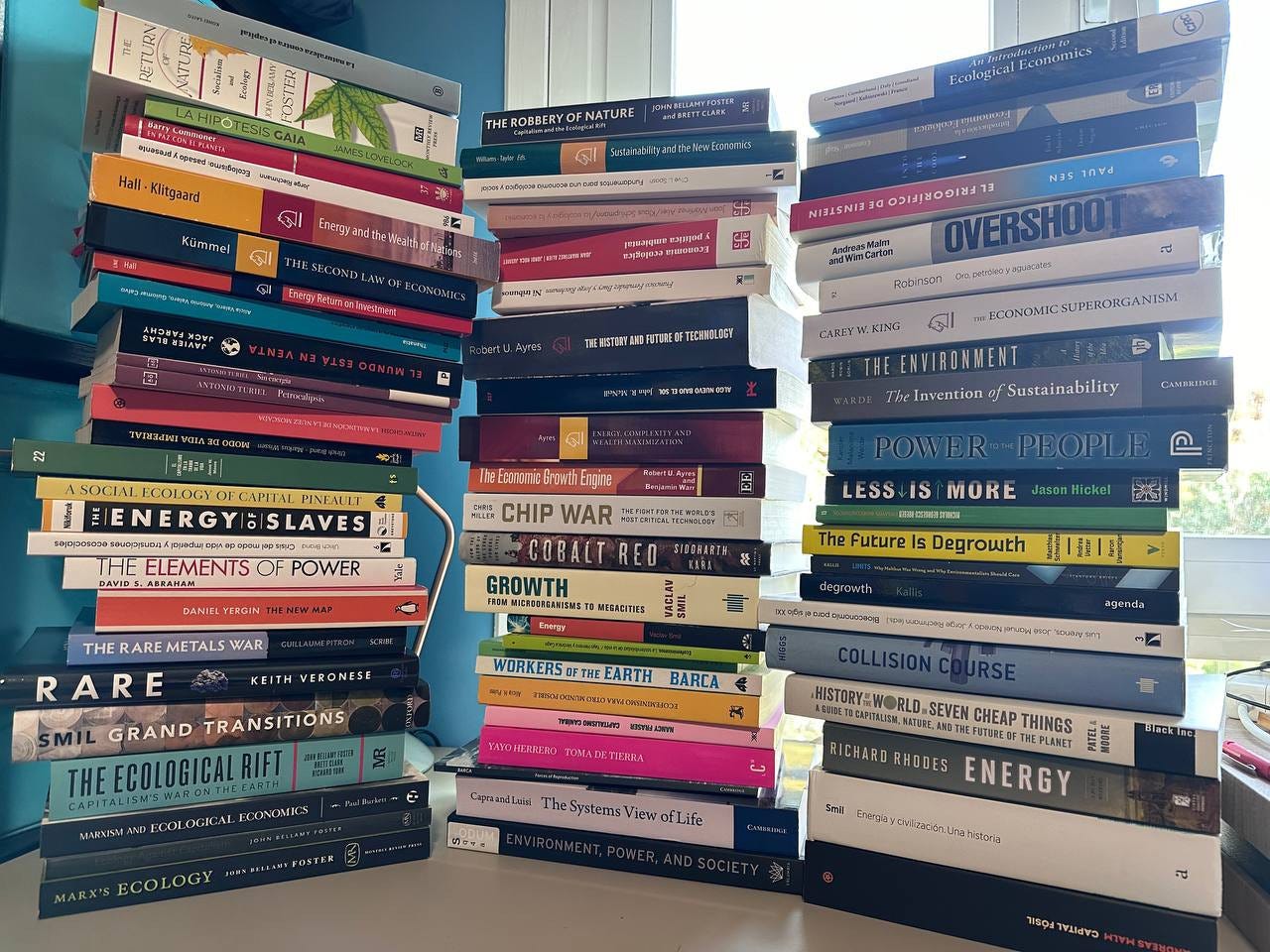

The Most Recommended Books on Energy and Ecological Economics

A list of the most useful books on energy, degrowth, ecofeminism, political ecology...

Several months ago, I created a thread on X and Bluesky with book recommendations on ecology and energy. I've now revisited that list and selected mostly books written in English. This post is the result.

These books are all valuable tools for understanding the current ecosocial crisis. I’ve carefully selected titles from my library that cover topics such as ecological economics, energy, degrowth, ecofeminism, political economy, science, natural resources, and more.

I hope you find it useful, too.

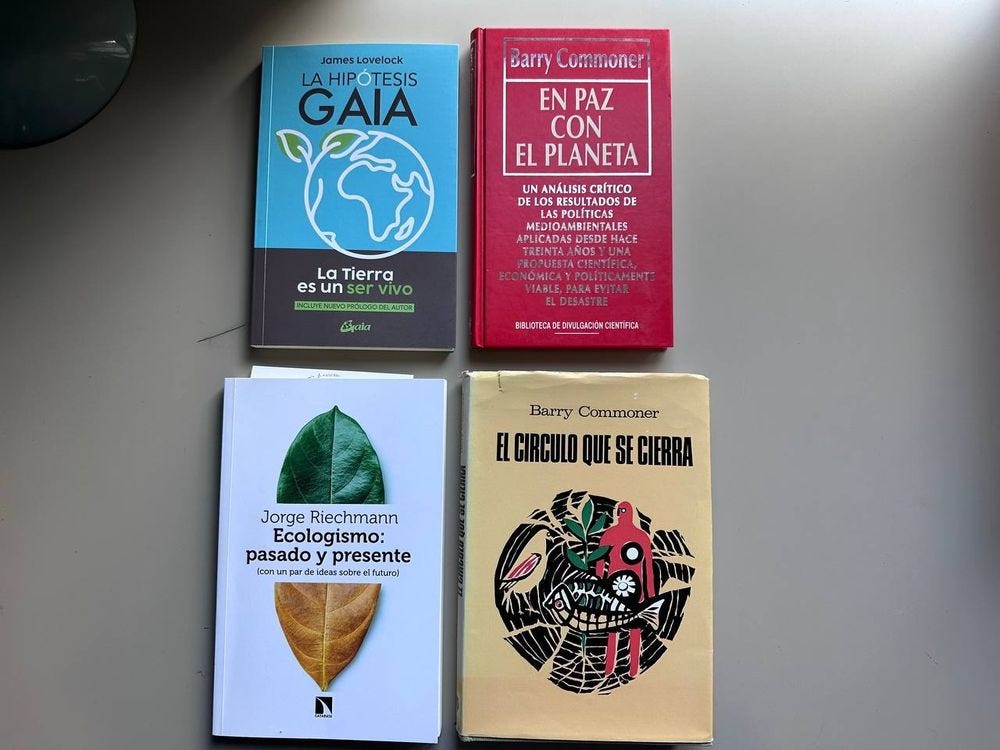

Let's begin with what we might call the authors of the ECOLOGICAL SPRING, as Fernández Buey, a Spanish philosopher, called it. Although there were precursors, such as Alexander von Humboldt in the 19th century, the ecological "awakening" began in the 1960s. I would highlight Rachel Carson, James Lovelock, and Barry Commoner.

Carson, Lovelock, and Commoner were all scientists. In Silent Spring (1962), Rachel Carson was the first to denounce the health effects of pesticides and other chemicals widely used in the industrial system. She sparked a massive debate that continues to this day. James Lovelock advanced the well-known Gaia hypothesis, which describes the Earth as a living organism. The renowned biologist Lynn Margulis also supported it. Once stripped of mysticism, this metaphor gave rise to Earth System Science, which today stands at the forefront of the study of our planet. And Barry Commoner, the least known but the most radical, wrote The Closing Circle (1971) and introduced highly contemporary ideas when discussing the limits of the economy and the overflow of the ecosphere by the technosphere. A recent anthology of his works has been published in Spanish.

A curious fact: the main introducer of Commoner’s work in Spain was Manuel Sacristán in the 1970s. Sacristán was already one of the leading Marxist thinkers in Europe and probably became an ecologist through this work. A recent compilation of his writings on science and ecology has been published.

I’ll conclude this section with the famous Limits to Growth report (1972) by the Club of Rome, published by a team of scientists led by Donella Meadows. It was the catalyst for the major debate on economic growth, further fueled by the 1973 oil crisis. Naturally, it remains highly relevant today.

A curious fact: mainstream economists—from Samuelson and Solow to Stiglitz, all neoclassical—responded critically to the report. This sparked a technically complex but highly interesting controversy. I’ll discuss it again (it’s covered in detail in my upcoming book).

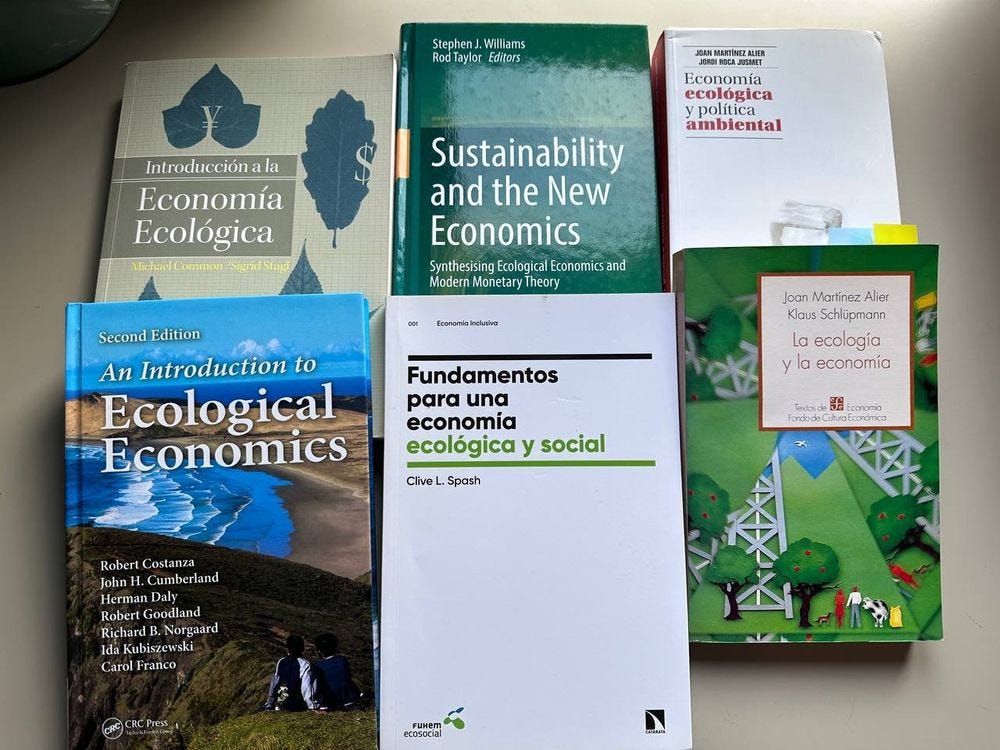

Let’s now move on to the PRINCIPLES of ecological economics. I’ve chosen these because they’re quite introductory and serve as a “compendium” of many core ideas in the field of ecological economics—or biophysical economics, which are generally interchangeable terms.

Herman Daly is one of the most renowned ecological economists, but instead of recommending a direct text, I suggest this simple handbook (An Introduction to Ecological Economics). The paradigm shift centres on recognising that the economy is a subsystem within the natural system.

There is also the Ecological Economics textbook by Common and Stagl. It’s very basic and, in my opinion, too conventional. However, it’s also an introductory resource available in Spanish, which gives it undeniable value.

Clive L. Spash is an economist who has spent decades exploring the boundaries of what we call ecological economics. This book (Foundations of social ecological economics: The fight for revolutionary change in economic thought) offers a broad overview of everything that has been written on the relationship between the economy and nature. He is highly critical of the neoclassical—or conventional—turn the field has taken in recent years.

Now we come to one of the founders of ecological economics in Spain: Joan Martínez Alier. These two books are real gems. The one co-authored with Roca (2013) is a simple, introductory textbook. I think it’s only in Spanish, while the other (1992) is a rich historical overview of thought in ecological economics. Alier’s book was originally published in English (1987), then in Catalan, and finally in Spanish (1992). He was trained in the UK and is probably the most internationally renowned Spanish ecological economist. He remains active and affiliated with the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology (ICTA) at the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

To wrap up, this book, edited by Stephen Williams, is a compilation of works on science, ecology, and economics from a critical perspective. They’re all introductory texts, which makes them easy to read. Some are also connected to modern monetary theory.

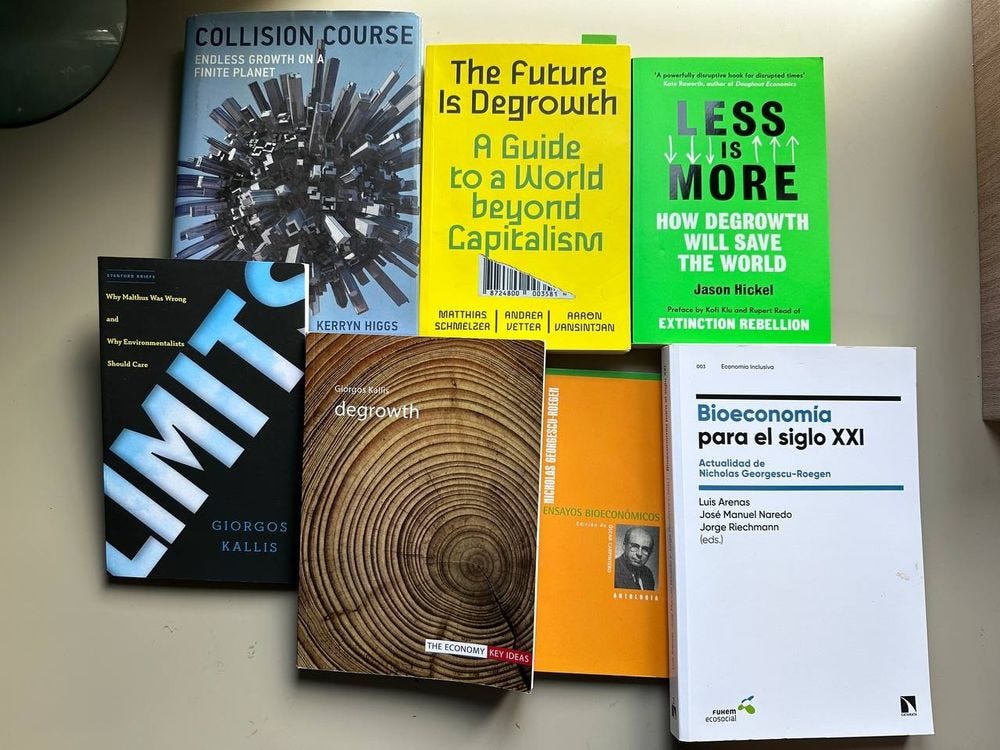

Let’s continue (Part 3) with books on degrowth and related topics—that is, on building an economic alternative that does not associate well-being with GDP. Or, more precisely, one in which resource and energy consumption is reduced to levels compatible with the planet’s limits.

One of the most recognised authors in this field is Jason Hickel, and his book Less is More—available in Spanish—is a great introduction to the topic. There’s an ongoing debate about the terminology used (whether degrowth, decrecimiento, or ecosocialism, for example).

Another well-known author is Giorgos Kallis, and his book Degrowth is also a fantastic introduction to the topic. It’s perhaps more technical and complex than Hickel’s but also more in-depth. In fact, both authors work together at ICTA-UAB, and any material by either of them is highly recommended.

We continue with The Future is Degrowth by Matthias Schmelzer, Andrea Vetter, and Aaron Vansintjan. This book offers a fantastic overview of the principles, values, and currents shaping the degrowth movement.

Now, we turn to Georgescu-Roegen, one of the founding figures of ecological economics. Although his work goes far beyond the degrowth movement, there’s no doubt that degrowth owes him a great deal. An anthology of his writings is available in Spanish, and a recent and excellent book features essays by various authors on his thought.

And we finish with a book on the debate around the limits to growth. There are many recent works on this topic, but I’ve chosen this one by Kerryn Higgs (Collision Course) because I find it very comprehensive. The Limits to Growth Revisited by Ugo Bardi is also a highly interesting read.

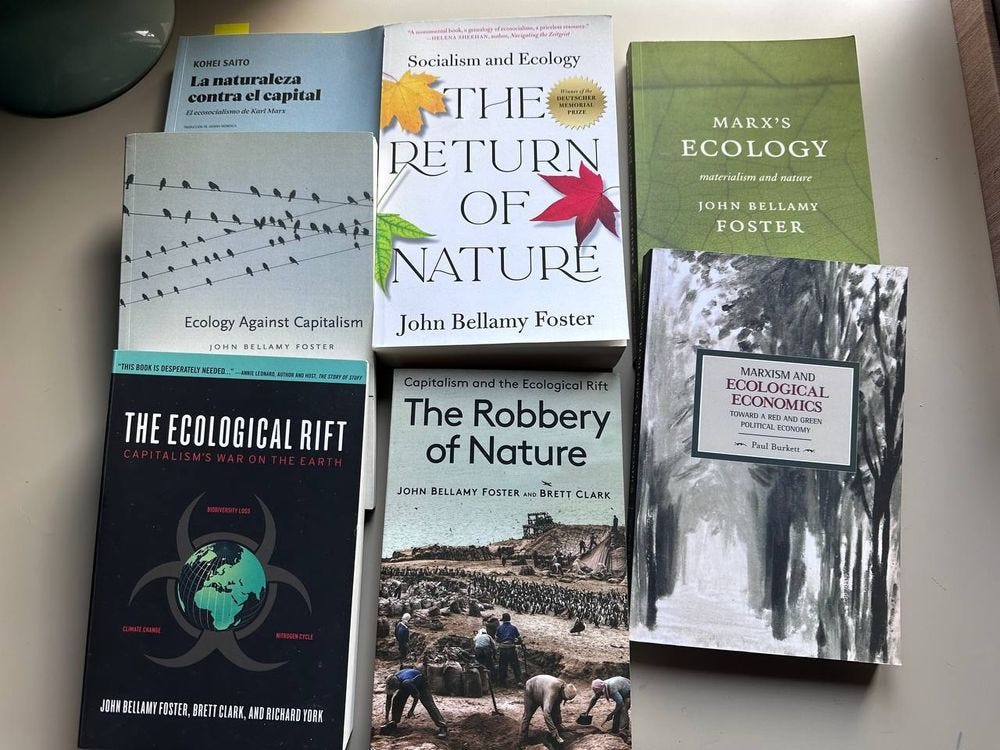

We now move on to Part 4: ECOLOGICAL MARXISM. This innovative current is mainly associated with the Monthly Review, which builds on the lessons Marx drew from reading the German chemist von Liebig in the 1860s. Before diving into the authors, I’ll offer a few considerations on the topic.

There’s little doubt that Marx was a productivist for most of his life who believed in the near-infinite expansion of the productive forces. However, there are scattered notes in which he refers to energy issues and, above all, to the natural limitation imposed by the land. Almost none of those notes by Marx were published during his lifetime. Therefore, it’s possible that an ecologist Marx began to emerge toward the end of his career. We know this happened with a Marx who became more aware of colonial and gender issues. Kevin Anderson’s The Late Marx’s revolutionary roads focuses precisely on this topic.

We know, for instance, that Marx read von Liebig with admiration—a chemist who helped elucidate the nutrient cycle in plants and the role of fertilisation. This led Marx to revise his views on land theory. This moment is often seen as the starting point of ecological Marxism. The more measured view, held by Martínez Alier, argues that this ecological reading did not seem to Marx “a relevant fact to explain the dynamics of capitalism.” However, Kohei Saito’s scholarly study concludes that Marx’s ecological perspective permeates the entire Capital, and that without it, the work cannot be fully understood.

Bellamy Foster’s ecological Marxism, in particular, focuses on the fundamental role of agri-food systems and what he calls the “Metabolic Rift.” Of all the recommended books, The Robbery of Nature is perhaps the most accessible starting point for new readers. These are essential works, but it would be irresponsible to deny that they deal with complex categories and analyses, and at times with rather dense philosophical concepts. They’re highly stimulating, but they do require a good deal of patience and dedication.

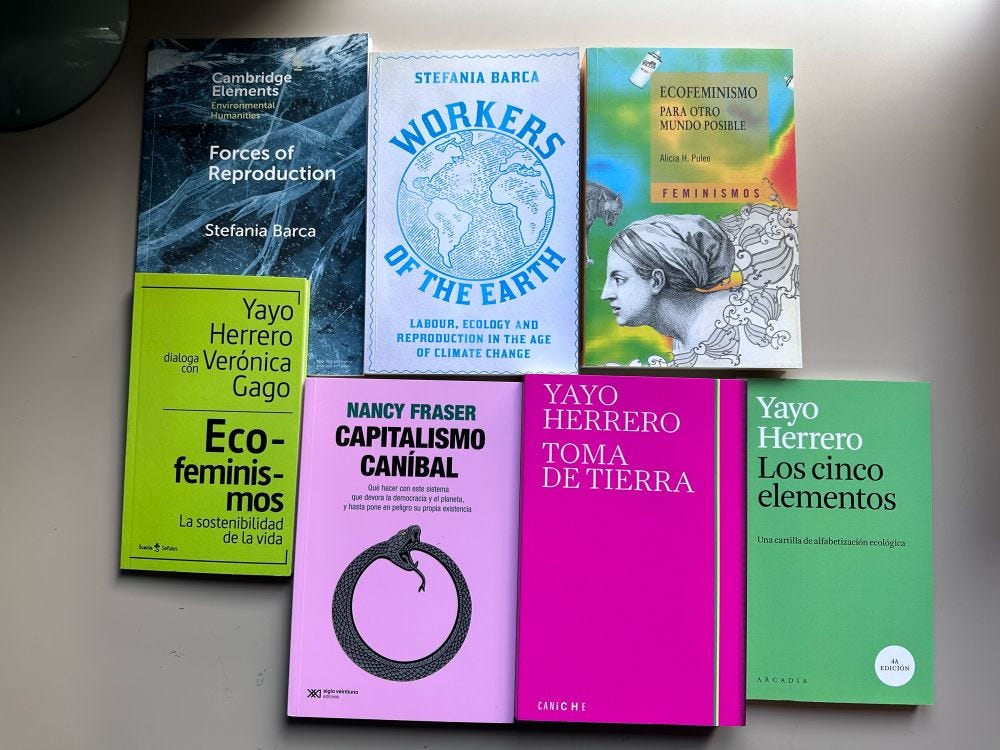

Now we move on to Part 5: ECOFEMINISM. The boundaries between different schools of thought are often blurry. Still, ecofeminism highlights a fundamental prerequisite of the economic system: its simultaneous reliance on care or domestic labour and on natural resources.

I recommend starting with Yayo Herrero's work, and Toma de Tierra is an excellent synthesis. I think it’s only in Spanish. There’s no theoretical entanglement around intersectionality—just a powerful reflection on how capital thrives on the cheap (or unpaid) labor of women.

One of feminism’s most outstanding contributions is the revitalization of the concept of “social reproduction” and the critique of traditional economic narratives, which tend to ignore care work and women. Stefania Barca’s work brings that theory to life with concrete, grounded examples.

Nancy Fraser argues that capitalism is more than just an economic system—it couldn't function without cheap, often female labor performing everyday tasks outside the market. Her theory on the dynamics of capitalism (and its historical phases) is both coherent and thought-provoking.

In Part 6, I’ve included works that invite us to rethink CHEAP PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION. The central idea is that capitalism relies on cheap energy and resources, which it secures through the exploitation and appropriation of subaltern classes, colonized regions, and nature itself.

This category has to begin with Jason Moore's excellent work. He offers a deep theory that analyses the world economy (in the Wallersteinian sense) while updating some key Marxist categories. It’s a challenging read at first, but immensely rewarding.

This other book, also by Moore but co-authored with Raj Patel, is much more accessible. It revolves around the same core idea: the system’s dependence on a steady supply of cheap resources and energy. The key follow-up question is: what happens when that cheap supply, limited by definition, runs out?

Ulrich Brand's books on the Imperial Mode of Living, using a different theoretical framework but grounded in the same idea, shed light on how consumption in wealthy countries relies on production chains rooted in labour exploitation and ecological damage.

What if our way of life is only possible because fossil fuels have become our “energy slaves”? And what will happen when there are no more slaves of this kind? This is the metaphor—quite common in ecological economics—that Andrew Nikiforuk explores in depth in this book The Energy of Slaves.

All societies can be understood as a great metabolism, with their need for incoming energy and outgoing waste, but when the logic of capital traverses this, it gives us a very specific kind of system. These are the relationships that Pineault’s book A Social Ecology of Capital analyses.

In part 7, we move on to books on ECOLOGICAL HISTORY, defined not as a history of science, but rather as what we might call “changes in the metabolism of societies” (energy, impacts, technologies, etc.).

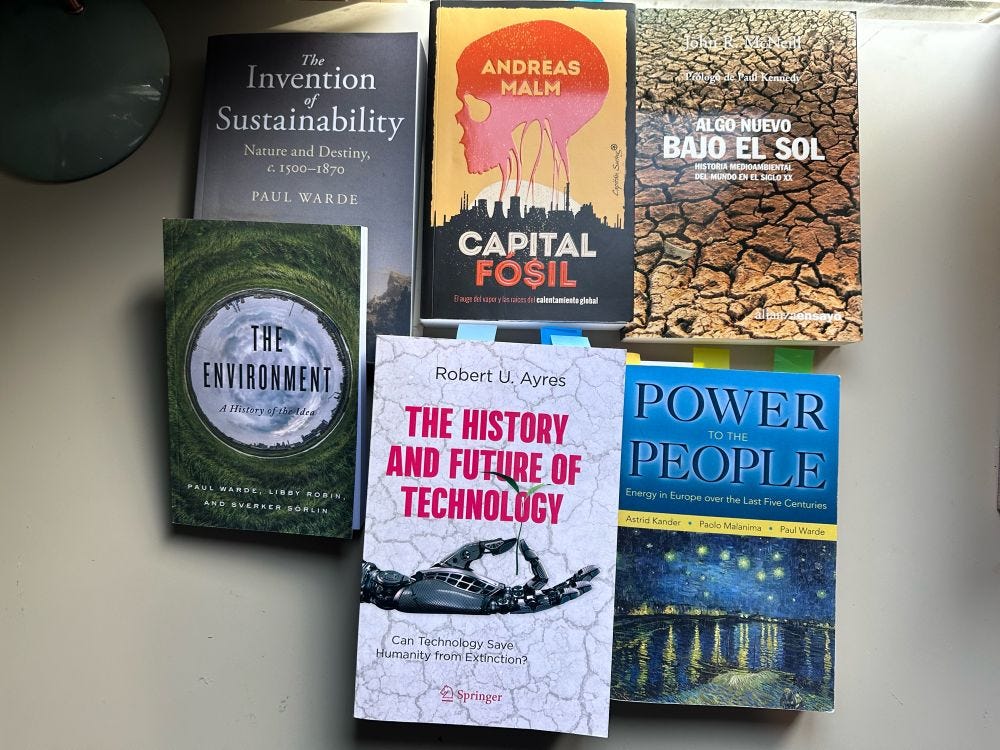

Although Vaclav Smil's work is more popular when it comes to studying the evolution of energy consumption—and he will appear later—for me, this collective history of the changes in Europe (Power to the People by Astrid Kander, Paolo Malanima and Paul Warde) is one of the best and most rigorous pieces written in recent years. I’d call it essential.

From one of the authors of the previous book, Paul Warde, we have these two histories on the evolution of the concept of sustainability and the creation of the notion of the “environment.” Both are thoroughly documented works that place the debates within specific historical contexts.

The recent The History and Future of Technology by Robert Ayres is closer to a conventional History of Science, but always with one eye on the energy question (efficiency, return, impacts…). That’s why I highlight it among the many options that deal with technological change.

Finally, Fossil Capital by Andreas Malm is a detailed study of the Industrial Revolution and the rise of fossil fuels in terms of their ecological and social impact. It’s a book to read slowly, as it is thoroughly researched.

Here I’m adding some books by Vaclav Smil. I’d highlight the encyclopedic Energy and Civilization: A History—not exactly bus reading—and the more introductory Energy: A Beginner’s Guide. The other two are extensions of his ideas into various economic and social topics.

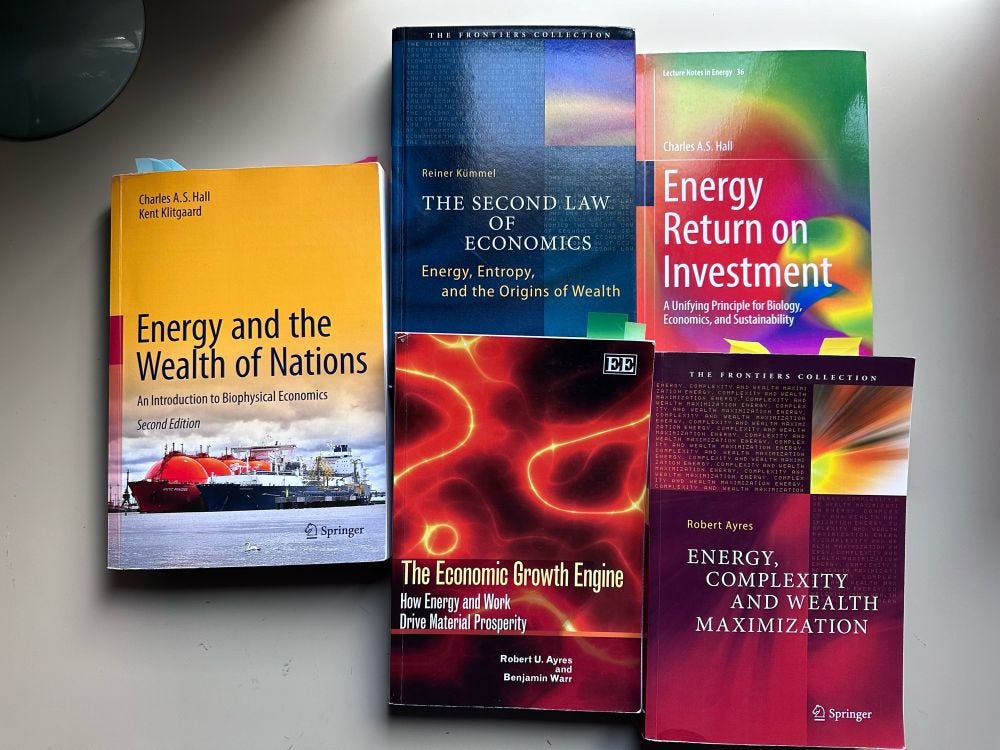

We continue with part 8, featuring books on ENERGY. This collection of challenging works is generally only recommended for specialists or those with at least a basic understanding of physics. Still, they are outstanding and much-needed contributions.

I’ll start with Energy and the Wealth of Nations by Charles A.S. Hall, probably the most well-known ecologist focused on economic issues. It’s an easy read, though somewhat disorganised—perhaps due to its ambition: it’s an encyclopedic book where you’ll find almost everything related to biophysical economics. A great place to start.

If the previous one feels overwhelming, here’s another book by the same author that offers a more focused take on a key point: Energy Return on Investment. The central question is: how much energy do we need to get energy? It’s a short, well-explained book that can also be a great entry point.

Robert Ayres is a physicist I mentioned would reappear. In The Economic Growth Engine, he critiques the neoclassical aggregate production function and questions the premise of economic growth within natural limits. It’s a complex and controversial topic, but essential reading for heterodox economists. There’s hardly a week I don’t look something up in this other book, Energy, Complexity and Wealth Maximization. It’s a kind of theory of everything: from quantum physics to biology, through ecology, economics, chemistry… Incredibly dense—especially in some sections—but incredibly comprehensive. Probably Robert Ayres’ most ambitious and thoroughly developed work.

Now, a kindred book to the previous one, though somewhat more accessible, by another physicist with a trajectory very similar to Ayres. The Second Law of Economics by Reiner Kummel focuses more directly on the relationship between energy and the economy, although it also touches on a wide range of fields.

Well, that’s all for now. I know I’ve left out many great books. Let me know if you think I should read or dive deeper into any of them—I’ll make time to do it! Thank you!

Thank you for a really fascinating list. I took up economics in my free time after returning from Nicaragua some 30 years ago, and ended up re-writing basic macroeconomics as mainstream school and undergraduate texts seem poor science and at often propaganda. Tasters in various languages and sample chapters are here https://sites.google.com/view/economyofwant and the whole e-book is free to download on certain dates.

I'd be interested to know if you think that any of the books you list do the same. Most 'alternative' economics books I've come across so far are critiques rather than replacements. Trying to shift what's taught to undergrads seems urgent to me, since they still seem to be reading texts that imply that perpetual growth is possible and unemployment is caused by workers not accepting lower wages.

EF Schumacher's 'Small is Beautiful' might be a worthy addition to this list.