Understanding the Trade War Between China and the United States: A Different Approach

A structural reading of the U.S.–China trade war, beyond tariffs and deficits, highlighting global power shifts, production chains, and competing development models

Amid the trade war between China and the United States, economic concepts have again dominated headlines. If, back in 2008, the public had to get familiar with terms like public debt, risk premium, or subprime mortgage, today the news revolves around tariffs, current account deficits, or currency devaluations. For most people, these are arcane terms, closer to mysticism than everyday life—reason enough for economists to explain what’s happening. However, much to the average citizen’s frustration, there is nothing close to consensus among economists; rather, there’s a broad range of theories and hypotheses suggesting different possible futures.

In this article, I propose a particular approach to help understand the current moment: to go beyond the official narrative and dominant theories of international trade to examine the structural roots of the trade war. Specifically, I emphasise that what is truly at stake is the position each country holds—and will hold—in the global economic system, particularly in the international division of labour.

The Symptom of Global Market Share

One of the most revealing indicators for understanding the current geopolitical dispute between the United States and China is the evolution of their shares in global merchandise trade. After World War II, North America and Europe accounted for more than 60% of global trade, while Asia barely reached 10%. This dominance by developed economies continued—and even intensified—until the 1970s, when they controlled over 70% of global trade. Since then, however, North America’s and Europe’s shares have steadily declined, now falling below 50%. In contrast, Asia has experienced a steady and accelerated rise, now accounting for over 40% of global trade.

Predictably, this trend is reflected in the two largest economies of those regions, the United States and China. The U.S. share of global trade has progressively decreased—from over 20% during the postwar period to barely over 8% today—while China has increased its position and now captures over 14% of world trade. This greater competitiveness of China compared to the U.S. is also evident in their bilateral trade: over half of the U.S. manufacturing trade deficit is explained by trade with China.

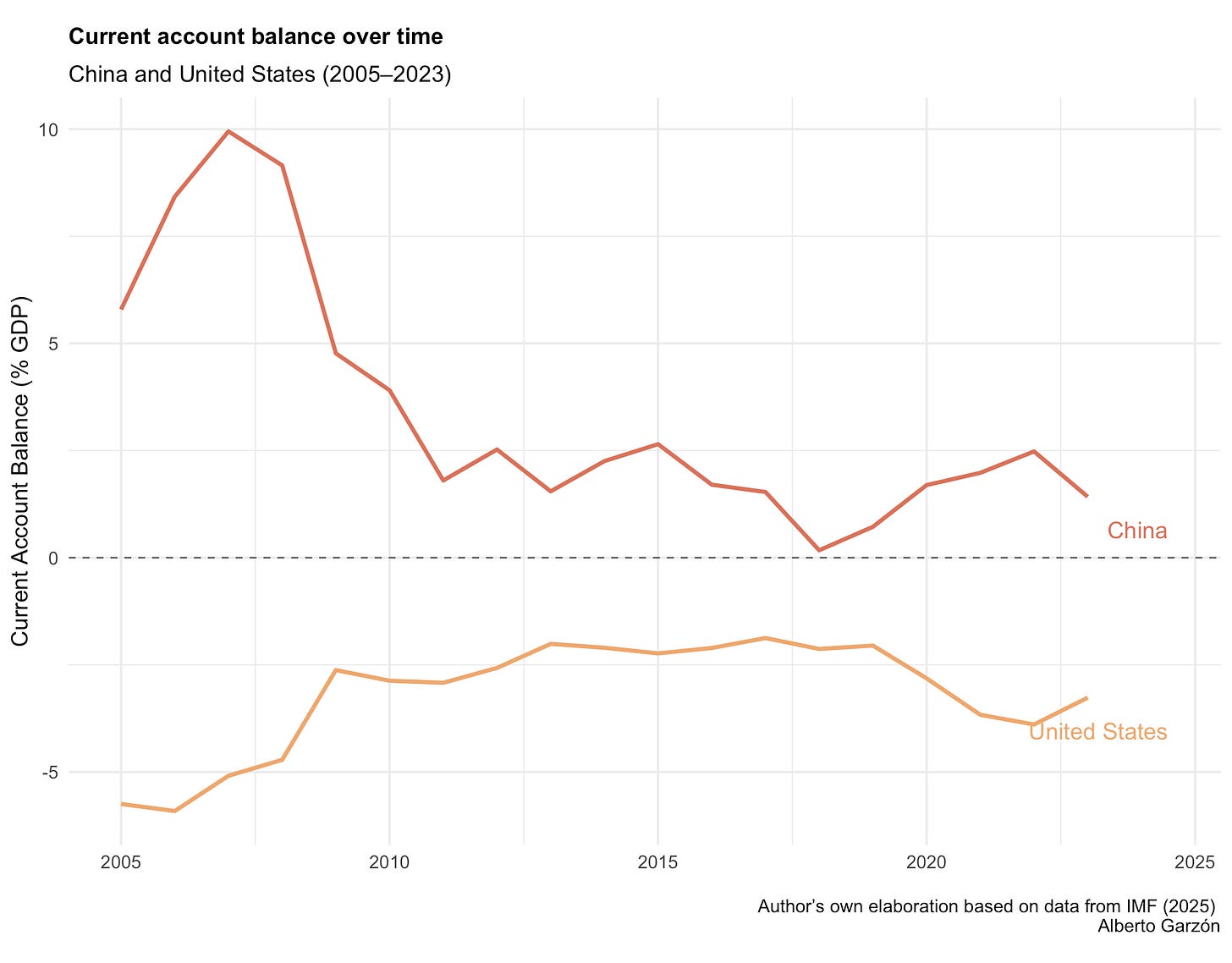

The most visible manifestation of this dynamic is the evolution of the U.S. current account balance, which expresses the difference between what U.S. companies sell in the global market and what U.S. citizens and companies purchase abroad. The U.S. has run persistent current account deficits since the 1980s, while China has consistently run surpluses, though decreasing in size. This situation, in which the U.S. imports far more than it exports, has concerned every U.S. administration, not just the current one, and is often attributed to alleged manipulation of China’s currency.

The Problem of the Three Balances

Under the “One, Big, Beautiful Bill” program, Donald Trump has recently announced historic cuts to public spending—up to $1 trillion—with the aim of reducing the enormous U.S. fiscal deficit. This adds to the cuts already implemented by Elon Musk at the head of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), which have resulted in mass layoffs and the closure of public agencies. Like all liberals who assume that the state operates like a capitalist company—and even more so when dealing with billionaire businessmen—their goal is to achieve a zero public deficit. However, even if they successfully reduced the fiscal deficit, if they simultaneously failed to reduce the trade deficit, they would be pushing citizens and companies in the United States into increasing private indebtedness.

To understand this, we need to recall that in macroeconomics, there is an accounting identity that states the sum of the private, public, and external balances must equal zero. Given that the external balance is the accounting inverse of the current account in the balance of payments, this means that if the public deficit is zero and the current account is in deficit, the private balance must necessarily also be in deficit. In other words, households and companies must take on debt. That is exactly what happened in Spain in the early 2000s and explains why achieving fiscal stability is difficult for countries with a current account deficit (importing more than they export) without simultaneously experiencing private debt bubbles.

Let's look at the evolution of these three balances for the U.S. economy. We see that the current account (the accounting inverse of the external balance) and the public balance have been running twin deficits since the beginning of the century. The current account deficit dates back to the early 1980s, while the public deficit has been a near-constant feature in U.S. economic history. This explains the particular interest in trying to reduce both deficits at once.

In reality, if Trump’s budget cuts are successful in their severity, there is one indirect way the current account balance could improve: through the population's impoverishment. The combination of public spending cuts and tariff increases will likely lead to slower economic growth and rising inflation, which could prompt interest rate hikes. In that scenario, an economic crisis and a drop in imports become the most likely outcome. Even without a dollar devaluation—and therefore without improved exports—the trade balance could improve simply because of the widespread impoverishment of the U.S. economy.

The Criminalisation of China’s Trade Surplus

The most common accusation is that China artificially keeps its currency undervalued to gain a competitive advantage, making its exports cheaper and allowing them to outcompete rivals, including U.S. products. This idea is appealing because it seems to place the blame for U.S. economic woes solely in the monetary realm. If true, it would mean that China must stop "manipulating the market" for the U.S. trade position to rebound.

This idea is based on the theory of comparative advantage formulated by David Ricardo, the English economist who first modelled how free trade can benefit all countries, even when there are significant differences in productivity levels. According to this theory, if a country runs a trade surplus (exports more than imports), an automatic adjustment mechanism is triggered: demand for its currency increases, causing it to appreciate, making exports more expensive and reducing the surplus. Conversely, a trade deficit leads to currency depreciation, making exports cheaper and imports more expensive, correcting the deficit. In this framework, trade imbalances are temporary, and the market, through exchange rates, acts as a correction mechanism. When this doesn’t happen in practice, it’s usually blamed on external interference, such as state intervention in currency markets.

There is, however, another way to interpret international trade. Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage was built on the earlier ideas of Adam Smith, who introduced the concept of absolute advantage. For Smith, international trade is justified when one country can produce a good more efficiently (i.e., at a lower absolute cost) than another. The key difference is that, as mentioned, Ricardo argued that even if a country has no absolute advantage in any product, it can still benefit from trade if it specialises in goods with a comparative advantage (i.e., a lower relative opportunity cost). Thus, from Ricardo’s perspective, free trade is mutually beneficial even between countries with vastly different productivity levels. In contrast, from the perspective of absolute advantage, free trade is detrimental to structurally less competitive countries, which would suffer permanent trade deficits. In sum, the theory of comparative costs sees the free market as a force that develops the participating economies. In contrast, the theory of absolute advantages views it as one that deepens structural differences.

The assumptions of these two theories—and their modern variants—are very different, as are the mechanisms they propose for correcting trade imbalances. Consequently, they lead to very different conclusions. While the comparative cost model expects market forces to correct these imbalances over time, the absolute cost model predicts that such imbalances will persist or even deepen. Although comparative cost theory offers various explanations for persistent trade imbalances, such as those of the U.S., real-world data seems to fit better with the theory of absolute costs. And this provides a very different diagnosis of the problem.

Economist Anwar Shaikh has spent over fifty years advocating the relevance of using the absolute cost approach to understand international trade. In 2021, he co-authored an academic paper with economist Isabella Weber in which they defended this approach in analysing U.S.–China trade relations. Their conclusion was unequivocal: the U.S. has structurally higher real costs than China, which is the true reason for its lower competitiveness and places the problem within the structure of the U.S. economy. Therefore, this problem cannot be solved solely through monetary mechanisms. From this perspective, the persistent current account deficit is not an anomaly caused by currency manipulation—or any other external interference—but the logical outcome of free trade between two structurally different economies.

All this implies that the economic strength of the U.S.—and its hegemony—is severely damaged at its foundations. China, in particular, represents a challenge to the post-WWII world order dominated by the U.S., and its growing share of the global market is merely a symptom of this shift.

China’s Industrialisation and Global Value Chains

After WWII, the U.S. actively promoted free international trade. Ironically, throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries, this country protected its emerging industries with tariffs, as I have explained here. However, once it achieved technological and productive supremacy, Washington began pressuring the rest of the world to open their markets to trade, just as Britain, the pioneer of the Industrial Revolution and modern capitalism, had done during its own development.

Nevertheless, many countries in the Global South understood that trade liberalisation alone was not enough to achieve development. That’s why, starting in the 1950s, some adopted a strategy of import substitution industrialisation, which was replaced with export-oriented industrialisation after the Latin American debt crisis. The first countries to show positive results with this new orientation were the so-called "Asian Tigers" (South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong). They succeeded in developing dynamic manufacturing industries that attracted capital from large Western transnational corporations. While the conventional narrative attributed their success to trade liberalisation and market reforms, later studies showed that the role of the state and industrial policy was essential to explain their growth. Some of the most influential research came from Robert Wade (1990), Ha-Joon Chang (2002), and Jesús Felipe (2013).

However, as early as the 1960s, transnational companies headquartered in industrialised countries began outsourcing production segments to reduce costs. This led to the first complex global value chains: production processes fragmented into multiple stages and distributed across different countries. In these chains, labour-intensive and low-tech segments were systematically relocated to developing countries, while capital- and technology-intensive tasks remained in developed countries. The availability of large amounts of cheap labour in Asia, along with its new basic industries, was key to the success of these corporate strategies.

Following a long process of economic reforms initiated in 1978, China joined the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001. Like other Asian countries, the state was central to industrial planning, financing, technology policy, and human capital formation. Thanks to this development, China integrated into global value chains and became the "workshop of the world," offering cheap export-oriented manufacturing, but also benefiting from a vast domestic market and the leadership of state-owned enterprises in key sectors. However, China was not content with producing low-value-added goods. Economic planning promoted a gradual upgrading of its industrial and technological base. In global value chain jargon, China pursued an ‘upgrading’ strategy, and Chinese companies quickly climbed the value chain. By the late 2000s, they were already competing in high-tech sectors—from telecommunications to renewable energy.

Geopolitics: Technology and Resources

The so-called "trade war" is, in reality, a superficial expression of a much deeper struggle. As developed economies rely on cutting-edge technologies and their exports, the trade war concerns control over these technologies and the strategic, scarce, and highly concentrated resources needed to develop and sustain them. This competition is unfolding globally, marked by climate change and new geopolitical tensions, including rising international migration and increasing risks to global food security.

In this scenario, it’s worth noting that global value chains are not fully global; they tend to be organised regionally. A hallmark of recent decades has been the rise of South–South trade, especially in the networks China has built with developing countries. For example, Chinese firms have taken on an increasingly active role in relocating production segments to African countries, many of which hold key reserves of strategic minerals essential for digital technologies and the energy transition.

The 2019 WTO report on global value chains highlighted this regional dimension in reconfiguring global production. On an aggregate scale—and across all productive sectors—by 2017, the international system was structured around three major hubs: China, the United States, and Germany. The U.S. economy was organised around ties with Mexico and Canada (both now heavily affected by tariffs); China structured its production networks primarily with Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea; while Germany did so with the broader European region, with growing involvement from Eastern Europe and even Russia and China, a topic I explored more deeply in this academic article.

Still, China’s relative weight in the global economy has grown recently. The country has advanced in controlling strategic segments of global value chains, not just as an assembly platform but also as a generator of knowledge and proprietary technology. China has gone from being “the world’s workshop” to challenging the lead in cutting-edge technological sectors, while strengthening South–South alliances, ramping up infrastructure investments through the Belt and Road Initiative, and expanding its influence in multilateral forums. Of particular relevance is the fact that in 2015, the Chinese government approved the “Made in China 2025” strategy, which focuses on industrial policy in high-tech sectors such as aerospace, maritime and rail transport, agricultural equipment, electric vehicles, and pharmaceuticals. China’s vast economy is increasingly organised around the very sectors in which Western countries have held an absolute advantage for decades, posing a real threat to them.

Unsurprisingly, this qualitative shift in China’s position has triggered a strategic response from the United States, which is now seeking to relocate parts of its production chains and protect critical sectors. In this context, trade tensions, restrictions on Chinese products in sensitive areas like digital technology, and the race for strategic minerals are not anomalies but expressions of a new phase in global geoeconomic conflict. Recall that J.D. Vance complained that neoliberal globalisation wasn’t designed for countries like China to climb the development ladder. In fact, the countries that climbed that ladder didn’t follow neoliberal rules. The problem now, for Vance, is that the U.S. will struggle to maintain its economic hegemony without resorting to greater use of threat and force. The U.S. at the start of the 21st century is like Britain at the start of the 20th: a declining empire, a frightened beast.

Conclusions

A quarter-century ago, I was fortunate to receive a copy of the book Competitiveness: Theory and Policy from economist Diego Guerrero, in which he offered a modern defence of Adam Smith’s theory of absolute costs, and thus a critique of the conventional trade theories taught in economics faculties. The book was dense and only suitable for specialists. Still, it opened up a line of inquiry that had previously been absent for me, since it barely warranted two lines in the most well-known International Economics textbooks. It helped me understand that if, at the national level, firms with lower costs tend to outcompete those with higher costs, the same mechanisms operate in international markets. Free markets do not naturally produce convergence between economies—more often, quite the opposite. For that reason, industrial policy, which entails state planning and intervention, is so vital for development strategies.

Unfortunately, these alternative approaches to trade remain unknown to most contemporary economists, who remain confined within the theories and ideas that justified neoliberal globalisation. Moreover, these conventional economists still wield too much influence over national and international policy, inevitably leading to disaster. Consider how a theory’s influence can transform a likely productivity issue in economic structure, as posited by the absolute cost theory, into a supposed competitiveness problem caused by monetary manipulation, as the comparative cost theory claims.

The blindness of most economists doesn’t stop there, since their minimal or nonexistent training in ecology adds further complications. After all, all international trade rests on abundant and cheap energy, especially from fossil fuels. The technological revolutions in transport that made long-distance trade profitable since the 19th century are highly dependent on this cheap fossil energy. Mineral resources for the ecological transition are also globally scarce, as highlighted by Alicia Valero, Antonio Valero, and Guiomar Calvo in their recent book Thanatia. And while most Western economists ignore these issues, perhaps assuming that companies will solve them through markets and prices, China has gotten ahead thanks to its combination of industrial policy and long-term strategy—a stark contrast to the short-term, ultra-liberal mindset that has dominated the West in recent decades. This struggle for leadership is only just beginning.

Understanding the trade war between China and the United States requires much more than following the tariffs or trade deficits. What is at stake is a global structural transformation of the world order, in which economic, technological, and energy hierarchies are being reconfigured globally. Clinging to outdated analytical frameworks or free-market dogmas only perpetuates strategic blindness. There is an urgent need to recover a critical perspective informed by history, geopolitics, and ecology, allowing us to diagnose today’s imbalances better. Only then might we seriously discuss how to compete and what kind of economic model we want to sustain on a planet with physical limits and growing tensions.